Imagine Britain with fewer nurses on wards, fewer carers in homes, fewer seasonal workers picking fruit, and fewer entrepreneurs building the next wave of jobs. That is not a hypothetical culture-war picture; it is the practical question underneath the slogan “stop immigration”.

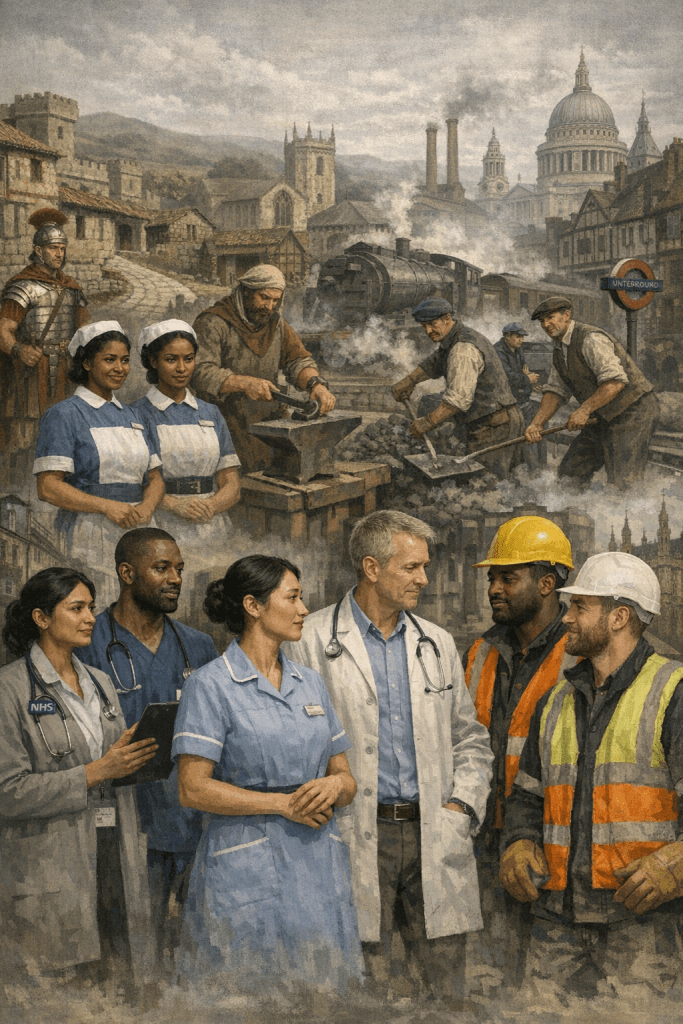

Because immigration is not a modern bolt-on to Britain. It has shaped how the country was built, how it functions, and how it pays for itself. If you remove immigrants from British history, you do not get the same Britain with fewer people; you get a different country altogether.

This is not about guilt or gratitude. It is about reality: who built things, who staffed services, and what happens to a country whose population is ageing faster than its workforce.

Part 1: Immigration has shaped Britain for centuries

Roman Britain: roads, towns, and early multicultural Britain

Britain’s first major inward movement followed Roman conquest. People arrived from across the Roman Empire, not only soldiers, but administrators, merchants, and craftspeople. Evidence from Roman York includes a high-status individual widely known as the “Ivory Bangle Lady”, understood to have migrated to Britain and often discussed in relation to North African ancestry.

What that era delivered was not just occupation, it was a new operating system for society:

- roads and transport routes

- towns and city life

- long-distance trade links

- organised administration and taxation

- early public infrastructure such as baths and drainage

The point is simple: Britain’s early urban growth was tied to the movement of people, skills, and networks, not isolation.

Medieval Britain: skills, trade, and finance

Medieval England also relied on inward movement. After 1066, Jewish communities came to England and became connected to royal finance and early lending structures. The National Archives notes Jewish arrival after 1066 in a context of state-building and access to finance.

As the economy developed, skilled migrants mattered too. Flemish textile workers were encouraged to bring specialist skills that strengthened cloth manufacture, a major driver of later English wealth.

These were not marginal contributions. They sat inside the growth of ports, towns, and an increasingly commercial economy.

Early modern Britain: refugees and engineers who changed industries

In the seventeenth century, Britain benefited from refugee migration. Huguenot arrivals are strongly linked to the development of silk and craft industries, including in Spitalfields, which became part of London’s manufacturing identity.

At the same time, Dutch engineering knowledge reshaped land and agriculture. Cornelius Vermuyden is documented as bringing land drainage and reclamation approaches and leading major projects in England’s marshlands.

So when people say “Britain made itself”, history suggests something more practical: Britain repeatedly imported skills that expanded what the country could build and produce.

Industrial Britain: the workforce behind infrastructure

Industrialisation demanded labour on a huge scale. Railway construction relied on large itinerant labour forces, commonly called navvies, numbering in the hundreds of thousands by the mid-nineteenth century.

Irish migration was particularly significant in nineteenth-century labour mobilisation and remained a recurring component of Britain’s industrial workforce.

This matters because it links directly to today. Britain grows when it has enough workers to build, repair, and expand infrastructure. Without labour supply, growth becomes a fantasy.

Post-war Britain: the NHS and rebuilding depend on migration

After 1945, Britain faced acute labour shortages. Migration from the Commonwealth and elsewhere became part of rebuilding the economy and staffing public services, especially healthcare. Windrush-era recruitment and the wider role of Caribbean communities in staffing hospitals are documented across historical sources on NHS workforce development.

This is the point many debates avoid: the NHS, now treated as a national icon, has always relied on overseas labour at scale.

Part 2: What immigration does for Britain today

History explains how we got here. The present shows what breaks if we pretend immigration is optional.

The NHS: not a footnote, a structural dependency

As of June 2025, around 325,000 out of 1.5 million NHS staff in England reported a non-British nationality, about 21 per cent, roughly one in five.

That is not an abstract “diversity” statistic. It means that if immigration fell sharply and international recruitment dried up, service delivery would be hit directly: rota gaps, longer waits, and greater pressure on existing staff..

Agriculture: food does not pick itself

In peak seasons, UK agriculture relies on a temporary workforce of around 75,000, 98 per cent of whom are recruited from elsewhere in the EU, according to the House of Commons Library’s analysis.

This is one of the clearest modern examples of how “just hire British workers” often fails in practice. It is not only wages, it is also location, seasonality, retention, and the speed at which farms need labour.

Construction and hospitality show similar patterns. ONS analysis indicates that around 10 per cent of the UK construction workforce was non-UK-born in 2018, rising to 40 per cent in London. In hospitality and tourism, migrants comprised around 24 per cent of hotel and restaurant staff in 2016, with nearly one in four tourism workers in London being foreign nationals. Across social care, education, and service industries, particularly in urban areas, migrants have filled persistent labour gaps that domestic supply alone has not met.

Innovation and jobs: migrants are overrepresented among founders

Although the foreign-born share of the UK population is under 15 per cent in many estimates, analysis of the 100 fastest-growing UK companies found that 39 per cent have foreign-born founders or co-founders.

That matters because it links immigration to what the economy needs most: new firms, new jobs, and productivity growth. It also connects the historical theme of skills transfer to modern entrepreneurship.

Part 3: A future with little or no immigration

This is where the debate shifts from opinions to demographics.

Population ageing and decline: the arithmetic problem

The Migration Observatory summarises ONS variant projections and notes that under a zero net migration variant, the UK population is projected to have declined from mid-2022. ONS methodology confirms that the zero net migration variant assumes zero net international and internal migration from the base year onwards.

In plain terms, without inward migration the UK becomes older faster and risks shrinking, leaving fewer workers supporting more retirees.

Public services and the tax base: the double pressure

A smaller workforce means fewer taxpayers. At the same time, an older population increases demand for healthcare and social care. That is the double pressure: higher need, lower capacity.

This is why the NHS point is so significant. When one in five NHS staff have non-British nationality, immigration is not a side issue. It is part of whether the system can function.

Labour shortages: where the pain shows up first

If immigration fell dramatically, the first visible impacts would likely be:

- harder-to-fill NHS and care roles

- seasonal agricultural labour gaps

- labour constraints in hospitality and parts of construction, especially in major cities

- slower delivery of building projects and infrastructure upgrades

These are not theoretical. They are the sectors where the UK already struggles to recruit and retain.

Cultural life: a quieter, narrower Britain

A UK with no new immigration would become less diverse over time. Multicultural city life would thin out, and many cultural institutions rooted in migrant communities would shrink.

It is sometimes claimed this would automatically increase social cohesion. That is not guaranteed. Cohesion is shaped by wages, housing, service quality, inequality, and political trust. A less diverse society can still be deeply unstable if those fundamentals deteriorate.

Conclusion: Britain has never thrived by shutting the door

Britain’s history shows repeated reliance on inward movement for labour, skills, and innovation. The present shows that key systems, especially the NHS and agriculture, still depend on it. The future shows that without immigration, the UK faces a demographic squeeze, a shrinking workforce, and rising pressure on public services.

So the honest question is not whether immigration creates challenges; it does. The honest question is whether Britain can realistically fund services, staff essential work, and sustain living standards in an ageing society without it.

History suggests the answer is no.

Sources: Official statistics, academic and think-tank studies have been used throughout. For example, Office for National Statistics projections, Migration Observatory reports, parliamentary research, and economic analyses provide the data and scenarios above. All numeric figures and assertions are cited in the text.

Leave a comment