Introduction

From the post-war period through to the late twentieth century, women’s social roles in the United States and the United Kingdom underwent profound structural change. In the 1950s, married women, particularly those with children, were strongly encouraged to remain outside paid employment and to derive fulfilment solely from domestic and caregiving roles. The full-time housewife was presented as both natural and psychologically protective.

This model has resurfaced in contemporary discourse under the label of the trad wife, often framed as a healthier alternative to modern working life. This article examines whether historical evidence supports that claim.

From the 1960s onward, female labour force participation rose sharply on both sides of the Atlantic, alongside changes in family law, education, and women’s legal rights. Using both quantitative data, such as suicide trends and employment statistics, and qualitative evidence from sociological and historical research, this analysis explores whether women confined to domestic roles between the 1950s and 1980s experienced poorer mental health outcomes than women with access to paid employment.

Domesticity and women’s mental health in the 1950s and 1960s

In the post-Second World War period, the dominant cultural narrative in both Britain and the United States idealised the suburban housewife. Popular media presented domestic life as comfortable, fulfilling, and emotionally complete.

Beneath this surface, however, many women reported profound dissatisfaction, emotional numbness, and depression. Betty Friedan famously described this as “the problem that has no name”, capturing a widespread but largely unspoken distress among middle-class housewives (Friedan, 1963).

Feminist scholars later argued that the isolation and monotony of full-time housewifery contributed to psychiatric illness in women. Chesler (1972) highlighted how women’s distress was frequently pathologised, with little acknowledgement of the restrictive social role of wife, mother, and homemaker.

Clinical evidence from the period supports these claims. Psychologists and general practitioners reported high levels of anxiety, fatigue, and depressive symptoms among housewives, often labelled informally as housewife syndrome. Treatment frequently consisted of tranquillisers rather than social or psychological support.

By the early 1960s, women were prescribed sedatives at far higher rates than men. Researchers have linked this pattern to social isolation and a lack of autonomy, rather than individual vulnerability (Haggett, 2009).

Cultural representations reflected this reality. The anxious, medicated housewife became a familiar figure in literature and music, as seen in the Rolling Stones’ “Mother’s Little Helper.” While stylised, these portrayals mirrored concerns expressed by clinicians and social researchers at the time.

It is important to acknowledge variation in women’s experiences. Oral history research indicates that some women found satisfaction in domestic life, particularly when relationships were stable and financial stress was minimal. However, even within these accounts, mental distress was common and often linked to factors such as marital breakdown, bereavement, or social isolation rather than fulfilment through housework alone (Haggett, 2009).

Mental health differences by age and social class

Women’s mental health outcomes in this period were not uniform. Research indicates that younger married women, particularly those with young children, are at higher risk of depression and suicide than older women whose children are independent (Brown, 1978).

Class also shaped experience. Middle-class housewives were more likely to report depression linked to loss of identity and social isolation, while working-class women, who were more likely to engage in paid or informal labour out of economic necessity, often demonstrated greater psychological resilience despite material hardship (Haggett, 2009).

This suggests that the mental health risks associated with domestic confinement were intensified where women lacked both economic necessity and social recognition for their labour.

Female suicide trends in the mid-twentieth century

Population level data reinforce concerns about women’s wellbeing during this period.

In England and Wales, female suicide rates rose steadily through the mid twentieth century, peaking in the early 1960s at approximately 10 to 12 deaths per 100,000 women (Kelly and Bunting, 1998). This represented one of the highest female suicide rates recorded in modern British history.

Contemporary psychiatric commentary explicitly linked women’s despair to restricted social roles and lack of autonomy (Miles, 1988).

In the United States, female suicide rates were lower than in Britain but still showed troubling patterns. A National Centre for Health Statistics report documented a steady rise in suicide among young women after 1950. Overall, US suicide mortality increased from around 10 per 100,000 in 1950 to approximately 13 per 100,000 by 1970 (National Centre for Health Statistics, 1967).

Many observers at the time attributed this rise to the limited life options available to women, particularly intelligent and educated women who were confined to domestic roles. Sociologist Jessie Bernard described the phenomenon of the “trapped housewife”, arguing that enforced dependency contributed to depression and suicidal ideation (Bernard, 1962).

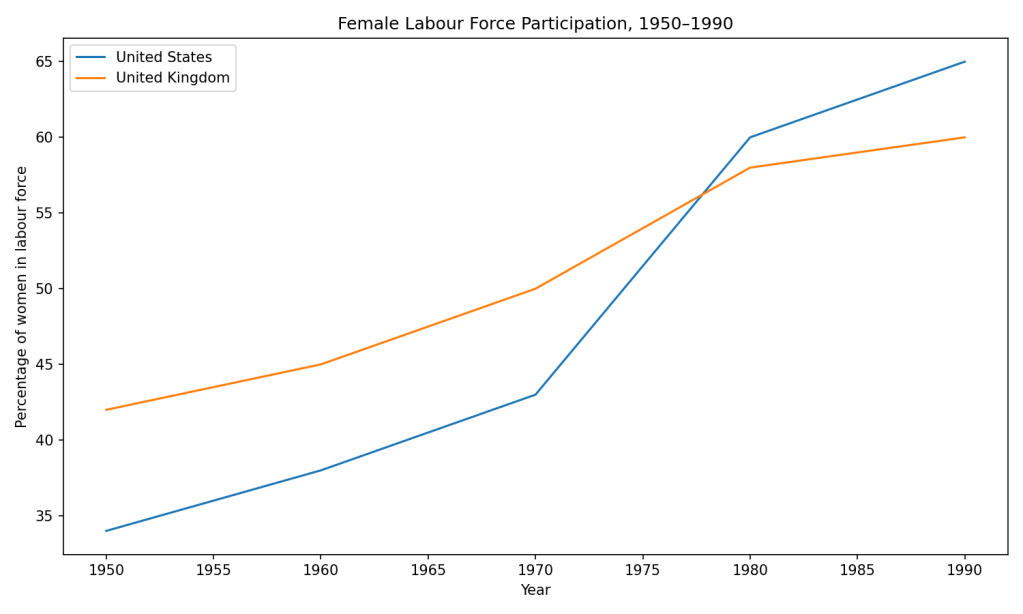

Figure 2: Female Labour Force Participation, 1950–1990

The rise of female employment and autonomy

From the 1960s onwards, women’s participation in paid work increased rapidly in both countries.

In the United States, approximately one third of women of working age were in the labour force in 1950. By 1980, this had risen to around 60 percent (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1999). The United Kingdom followed a similar pattern, with participation rising from around 42 percent in 1951 to nearly 58 percent by 1981.

Married women with children drove much of this change. Workforce participation among mothers of young children, previously rare and socially discouraged, became increasingly common.

Several factors contributed to this shift. Economic demand during the post-war boom created labour shortages. Women’s educational attainment rose. Fertility rates declined, shortening the period of full-time childcare. Legal reforms reduced discrimination and expanded women’s rights to employment and equal pay.

While many women worked part-time, particularly in Britain, paid employment nevertheless offered something domestic life often did not: income, social connection, identity, and a degree of independence.

Sociologist Arlie Hochschild observed that for many women, work functioned as a counterbalance to domestic stress, even while creating new pressures associated with the so called second shift.

Suicide and mental health outcomes after increased female employment

If expanded employment and autonomy benefited women’s mental health, this should be reflected in population outcomes. The data suggest that it was.

In England and Wales, female suicide rates declined by approximately 40 percent between the mid-1960s and mid 1970s (Kelly and Bunting, 1998). While the detoxification of domestic gas reduced lethality, evidence indicates that suicide attempts also declined, not simply deaths.

Psychiatric hospitalisation of women for severe depression fell, and by the late 1970s, surveys found that housewives were no more likely to report depression than employed women, a reversal of earlier patterns.

In the United States, suicide rates peaked around 1970 and declined through the 1980s. Women followed a similar trajectory. Studies of women aged 25 to 44 showed improved outcomes by the 1980s compared with the previous two decades.

A pivotal study by Burr, McCall and Powell Griner (1997) found that by 1980, areas with higher labour force participation among married women had lower female suicide rates. Women’s role accumulation had become protective rather than harmful.

Legal autonomy and women’s survival

One of the strongest indicators of the relationship between autonomy and mental health comes from family law reform.

Stevenson and Wolfers (2003) analysed the introduction of no fault divorce laws across US states. They found a long-term reduction of around 20 percent in female suicide following reform, alongside reductions in domestic violence and female homicide by partners.

The authors argue that legal and economic independence offered women a credible alternative to despair. Where exit routes existed, suicide declined.

This finding is directly relevant to modern trad wife narratives. Dependency without autonomy increases risk. Choice with security reduces it.

Contemporary relevance

Modern research continues to support the historical finding that autonomy and choice are central to women’s mental wellbeing. Studies show that women experiencing financial dependency or limited exit options face higher risks of depression, anxiety, and coercive control.

While some women today choose domestic roles, this choice exists within a legal and economic framework shaped by the gains of the twentieth century. The historical evidence demonstrates that when domesticity is not accompanied by autonomy, mental health outcomes worsen.

Practical implications for policy and practice

The historical evidence points to clear lessons that remain relevant today:

- Economic independence is a protective factor for women’s mental health

- Legal autonomy reduces extreme distress and suicide risk

- Social isolation, not paid work, is a consistent predictor of poor mental health

- Domestic labour without recognition, income, or exit options increases vulnerability

Supporting women’s wellbeing therefore requires:

- Affordable childcare and flexible working arrangements

- Legal and financial protections for women in unpaid domestic roles

- Mental health services that recognise coercive control and economic abuse

- Valuing domestic labour without enforcing dependency

Conclusion

Between the 1950s and 1980s, women’s mental health outcomes in the United States and United Kingdom improved alongside expanded access to paid employment and legal autonomy.

Female suicide peaked during the height of enforced domesticity and declined as women’s roles diversified. While causation is complex, the trajectory is consistent. Women’s wellbeing improved when autonomy increased.

The historical record does not support the claim that women were safer, healthier, or happier when confined to the home. The trad wife narrative romanticises a period associated with elevated depression, heavy medication, and limited escape routes.

This history matters because it reminds us that choice is protective, dependency is not, and women’s mental health has always been shaped by the structures that govern their lives.

Why this matters now

History shows that women’s mental health improves with autonomy, not dependency. Romanticising enforced domesticity risks repeating the psychological harm of the past.

References

Burr, J.A., McCall, P.L. and Powell Griner, E. (1997) Female labour force participation and suicide. Social Science and Medicine, 44(12), pp.1847 to 1859.

Chesler, P. (1972) Women and Madness. New York: Doubleday.

Friedan, B. (1963) The Feminine Mystique. New York: W.W. Norton.

Haggett, A. (2009) Desperate housewives and the domestic environment in post war Britain. Oral History, 37(1), pp.53 to 60.

Kelly, S. and Bunting, J. (1998) Trends in suicide in England and Wales. British Journal of Psychiatry, 173, pp.558 to 564.

Miles, A. (1988) Women and Mental Illness. Brighton: Harvester Press.

National Center for Health Statistics (1967) Suicide in the United States 1950 to 1964. Washington DC.

Stevenson, B. and Wolfers, J. (2003) Bargaining in the shadow of the law. NBER Working Paper No. 10175.

US Bureau of Labor Statistics (1999) Women in the Labor Force A Databook. Washington DC.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly

Leave a comment