Introduction

The twenty-first century has brought both unprecedented freedoms and persistent ambivalence for single women. Legally and structurally, women can now access education, professions, banking, and property without male mediation. They can also remain in employment during marriage or pregnancy, freedoms secured only in the later decades of the twentieth century. At the same time, cultural discourses surrounding singleness continue to fluctuate between empowerment and stigma. Some celebrate “single positivity,” while others reinscribe narratives of loneliness or incompleteness. This chapter critically evaluates these contradictions, situating the contemporary experiences of single women within wider demographic, cultural, and psychological shifts.

Demographic Change

Marriage rates across the Western world have declined sharply since the late twentieth century. In Britain, fewer than half of adults were married by 2020, with cohabitation, divorce, and life-long singleness increasingly common (ONS, 2021). Women now marry later, typically in their thirties, and many remain unmarried across the life course.

Fertility patterns have shifted accordingly. A growing proportion of women remain childfree, while assisted reproductive technologies such as IVF have enabled some single women to become mothers independently, though access varies by income and geography (HFEA, 2022). These demographic changes highlight that singleness is not marginal but a mainstream life trajectory.

Autonomy and Higher Education

Women’s presence in higher education is now firmly established, with female enrolments outnumbering male students in most UK universities (HESA, 2023). This structural change has provided single women with professional credentials and economic security. Elyakim Kislev (2025) notes that in a “post-materialist era,” higher education and career fulfilment are increasingly prioritised over marriage, reflecting shifts in values towards freedom and self-realisation.

Employment, Finance, and Structural Independence

By the twenty-first century, women had long surpassed the key barriers of earlier generations. Marriage bars were abolished mid-twentieth century, maternity protections are now statutory, and the Equality Act 2010 reinforced equal pay and protection against sex discrimination. Financial independence, once restricted, is now normalised: women open bank accounts, take out loans, and secure mortgages without needing male guarantors, a right secured only in the 1970s.

Single women therefore enter housing and investment markets as independent agents. Yet inequalities remain. Single-income households face structural disadvantages in high-cost housing, women’s pensions are often lower due to wage disparities, and single mothers remain disproportionately at risk of poverty (McKee, 2020).

The Psychology of Singlehood

Research on singlehood highlights the distinction between voluntary and involuntary singleness. Slonim and Schütz (2015) show that women who identify as single by choice often report higher life satisfaction and autonomy than those who perceive themselves as single by circumstance. Pepping and MacDonald (2019) link long-term involuntary singlehood to attachment styles, yet this view risks pathologising autonomy.

By contrast, Kislev (2019, 2025) demonstrates that voluntary singlehood is increasingly associated with higher happiness and fulfilment, especially when framed within post-materialist values of freedom and self-direction. This aligns with DePaulo’s (2011, 2015, 2023) critique of “singlism”; the stereotyping and marginalisation of singles, which persists despite evidence of flourishing single lives.

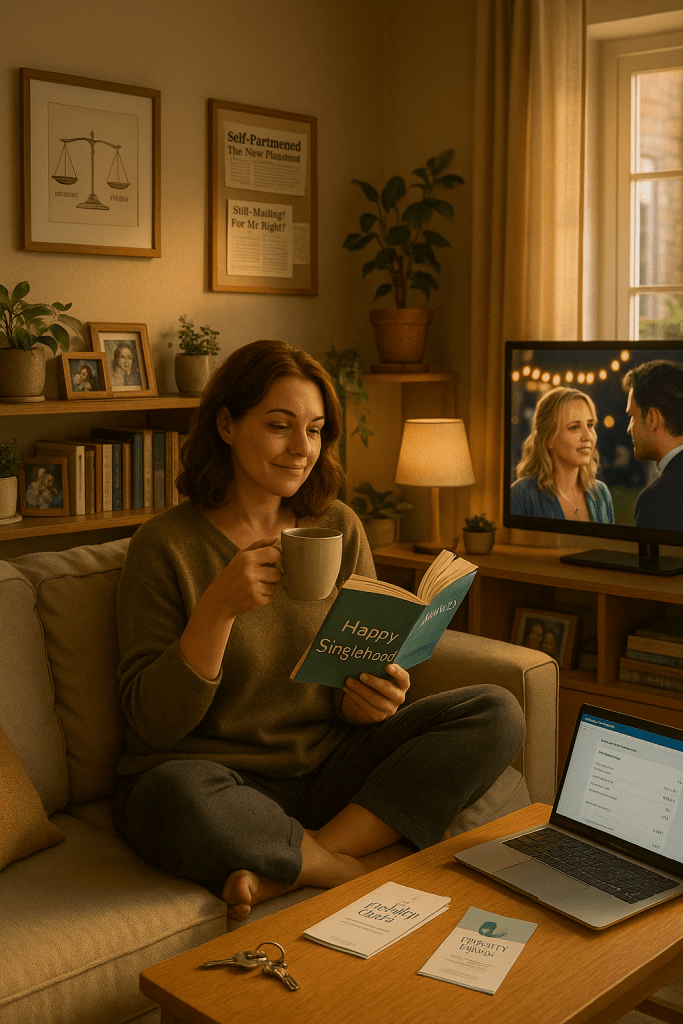

Cultural Narratives: Between Positivity and Stigma

Cultural scripts about singlehood remain contradictory. On the one hand, a rising discourse of single positivity emphasises choice, empowerment, and self-partnering (The Guardian, 2021; Watson, 2019). Emma Watson’s redefinition of herself as “self-partnered” epitomised a generational shift towards reframing singlehood as a conscious, affirming identity.

On the other hand, cultural pressures endure. Kislev (2025) and Moore & Radtke (2015) argue that single women must continually negotiate cultural norms that present marriage as the default, forcing them to justify their status as either temporary or deficient.. Lahad (2017) describes singleness as a “non-scheduled status passage,” resisting society’s expectation of linear life progression.

Recent journalism also complicates the narrative. The Guardian (2021) reported that rising numbers of women are deliberately choosing singlehood as preferable to unequal partnerships, while The Atlantic (2025) critiques a growing cultural “obligation of positivity”, the expectation that single women must present their status as empowering, even when it is ambivalent.

Hidden Barriers in the Twenty-First Century

Despite structural freedoms, society remains slow to adapt to the reality of widespread singleness, producing material and cultural penalties.

Single Supplements and Travel Costs

In tourism, the most visible disadvantage is the single supplement. Solo travellers frequently pay 25 %–100 % more per head than couples for accommodation and package holidays. Hotels and resorts justify this on cost grounds, but in effect it penalises women for travelling alone. Some tours even require paired bookings, effectively excluding singles. While niche firms offer roommate-matching schemes, this can be uncomfortable or unsafe for women. The practice constitutes a hidden tax on leisure and mobility, reinforcing inequality.

Other Financial Penalties

Beyond holidays, single women face a “single penalty” across multiple domains:

- Housing: higher per-capita rents and mortgages due to single incomes.

- Utilities and insurance: fewer bulk discounts and occasionally higher per-person charges.

- Consumption: retail and subscription deals designed for households make single living more expensive.

- Tax and benefits: systems often advantage couples through joint allowances and spousal benefits.

- Pensions and care: single women cannot rely on spousal pensions, and care costs fall entirely on them.

These financial penalties accumulate, producing structural disadvantage even in a context of legal equality.

Loneliness, Community, and Stigma

Barriers are also psychological and social. The Guardian (2024) notes that young single women are reporting heightened loneliness, exacerbated by declining communal spaces and digital fragmentation. BBC Worklife (2022) documents persistent “single shaming,” where unpartnered women are questioned, pitied, or judged as incomplete.

Academic research confirms this. A BMC Psychology (2021) study found that stigma around singlehood can negatively impact wellbeing, with women who internalise these judgements reporting higher depressive symptoms and lower life satisfaction. This shows how social prejudice still imposes mental costs on singlehood, despite structural freedoms.

Critical Evaluation

The twenty-first century demonstrates the paradox of autonomy and ambivalence. Single women have unprecedented freedoms in law, education, and employment, yet continue to face systemic disadvantages in consumption, housing, holidays, and pensions. Moreover, cultural expectations remain slow to shift: single women must still negotiate stigma, or conversely, the pressure to present themselves as empowered.

Thus, equality in formal rights has not eradicated inequality in lived experience. True autonomy requires addressing these hidden penalties and rethinking social and economic systems still modelled around couples.

Conclusion

Single women in the twenty-first century enjoy freedoms unimaginable to earlier generations. Yet autonomy is tempered by enduring financial, cultural, and social barriers. Single supplements, housing inequalities, stigma, and loneliness reveal that society still lags behind demographic reality. Singleness is no longer marginal, but until institutions adapt, single women will continue to pay, financially, socially, and emotionally, for their independence.

References

- BBC Worklife (2022) ‘Single shaming: Why people jump to judge the un-partnered’. BBC Worklife, 5 April. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/worklife/article/20220405-single-shaming-why-people-jump-to-judge-the-un-partnered (Accessed: 8 October 2025).

- BMC Psychology (2021) ‘Singlehood stigma and mental health outcomes’. BMC Psychology, 9, 75. Available at: https://bmcpsychology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40359-021-00635-1 (Accessed: 8 October 2025).

- DePaulo, B. (2011) Singlism: What it is, Why it Matters, and How to Stop it. DoubleDoor Books.

- DePaulo, B. (2023) ‘Single and flourishing: Transcending the deficit narratives of single life’, Journal of Family Theory & Review, 15(3), pp. 389–411.

- Guardian (2021) ‘Why are increasing numbers of women choosing to be single?’ The Guardian, 17 January. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2021/jan/17/why-are-increasing-numbers-of-women-choosing-to-be-single (Accessed: 8 October 2025).

- Guardian (2024) ‘Young single women lonelier than ever as community declines’. The Guardian, 21 August. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/article/2024/aug/21/young-single-women-lonelier-than-ever-community (Accessed: 8 October 2025).

- HESA (2023) Higher Education Student Statistics: UK, 2021/22. Cheltenham: HESA.

- HFEA (2022) Fertility Treatment 2021: Trends and Figures. London: HFEA.

- Kislev, E. (2019) Happy Singlehood: The Rising Acceptance and Celebration of Solo Living. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Kislev, E. (2025) ‘Being single in the twenty-first century’, in Mortelmans, D., Bernardi, L. and Perelli-Harris, B. (eds) Research Handbook on Partnering Across the Life Course. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 129–147.

- McKee, K. (2020) ‘The precarity of single women’s housing’, Housing Studies, 35(6), pp. 967–985.

- Office for National Statistics (ONS) (2021) Families and Households in the UK: 2020. London: ONS.

- Pepping, C.A. and MacDonald, G. (2019) ‘Adult attachment and long-term singlehood’, Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, pp. 105–109.

- Slonim, G. and Schütz, A. (2015) ‘Singles by choice differ from singles by circumstance’, Association for Psychological Science Convention, New York.

- Tyler, I. (2013) Revolting Subjects: Social Abjection and Resistance in Neoliberal Britain. London: Zed Books.

Leave a comment