Introduction

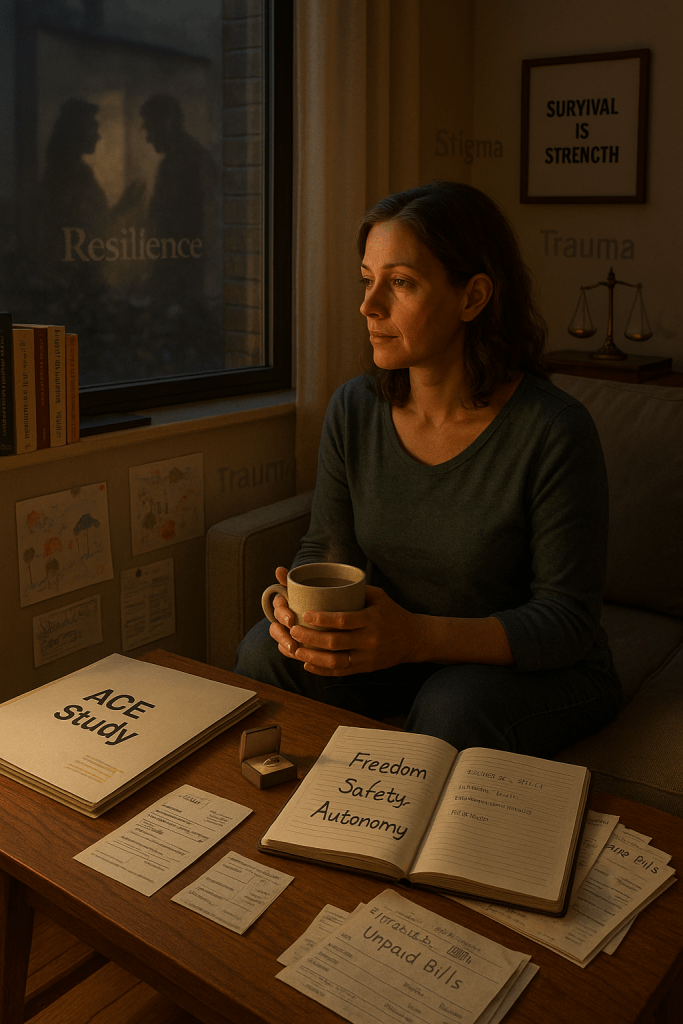

While many women in the twenty-first century embrace singleness as a form of autonomy or lifestyle choice, others arrive at it as a protective strategy. Experiences of childhood abuse, domestic violence, coercion, or intergenerational trauma often shape decisions to avoid intimate partnerships. Historically, marriage itself exposed women to potential harm, as coverture legally subordinated wives to husbands, making economic and legal escape from abuse difficult. Today, despite formal rights and protections, some women continue to view singlehood as the safest path. This chapter explores the intersections of trauma, autonomy, and protective singleness.

Historical Context: Marriage as a Risk Site

For much of history, marriage was legally and economically binding. Under coverture, a wife’s property and legal identity merged with her husband’s (Holcombe, 1983). This meant women had few avenues of escape if subjected to cruelty, violence, or exploitation. Divorce was inaccessible to most until the late nineteenth century, and even then heavily stigmatised.

The result was that singleness, particularly for widows and spinsters, sometimes provided greater security than marriage. As Shanley (1989) notes, the patriarchal structure of Victorian marriage created conditions in which domestic abuse was often hidden and tolerated, whereas unmarried women at least retained legal control over their earnings and property. The historical memory of marriage as a site of vulnerability continues to resonate in contemporary narratives of protective singleness.

Childhood Trauma and Adult Attachment

Research on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) shows that early exposure to abuse, neglect, or household dysfunction increases the likelihood of difficulties in adult relationships (Felitti et al., 1998). More recent studies confirm that childhood interpersonal trauma is strongly associated with later relational avoidance and difficulties forming trust (Smith et al., 2025).

Survivors of childhood sexual or physical abuse may develop insecure or avoidant attachment styles, characterised by distrust, fear of intimacy, or emotional withdrawal (Colman and Widom, 2004). In this context, singleness often becomes a protective strategy. Rather than signalling deficiency, it provides autonomy, predictability, and safety.

Intimate Partner Violence and Revictimisation

Contemporary research shows that women who experience intimate partner violence (IPV) often avoid remarriage or cohabitation as a means of self-protection. Anderson and Saunders (2003) observed that many survivors of abuse cite singlehood as empowering, providing freedom from control and violence.

Recent scholarship confirms this pattern: Kislev (2019) notes that for some, singlehood represents not just independence but resilience in the aftermath of harmful relationships. Qualitative accounts show that many women frame remaining single as a refusal to re-enter coercive dynamics, even in the face of economic hardship (Moore and Radtke, 2015).

Intergenerational Trauma and Patterns of Avoidance

Trauma is not only individual but also intergenerational. Danieli (1998) highlights how trauma can be transmitted across generations through silence, inherited coping behaviours, or distrust of intimate relationships. Daughters of abused women may internalise suspicion of men, adopt hyper-independence, or avoid marriage altogether.

Cultural memory plays a role too. Historical associations of marriage with dependency and risk have shaped feminist critiques of matrimony as a patriarchal institution. Delphy (1984) argued that marriage often facilitated women’s exploitation, positioning singleness as a form of resistance. Thus, protective singleness operates both as an individual response to trauma and a structural critique of marriage as historically unsafe.

Contemporary Narratives of Protective Singleness

Qualitative research highlights how many women describe singleness as a choice rooted in safety and control. Reynolds and Wetherell (2003) found that single women frequently emphasised peace, freedom, and avoidance of harm as key benefits of their status. Budgeon (2016) likewise shows that women’s narratives often frame singlehood not as absence, but as autonomy.

Contemporary journalism and surveys reinforce these findings. The Guardian (2024) reported that many young women, particularly those with negative past relationship experiences, prefer singleness to unequal or unsafe partnerships. This reflects a growing recognition that singlehood may provide psychological and physical security, even in contexts that still stigmatise it.

Hidden Costs: Trauma, Stigma, and Mental Health

Protective singleness, while providing autonomy, often carries hidden costs. Women who remain single due to trauma sometimes report isolation or social stigma. BBC Worklife (2022) describes persistent “single shaming,” where unpartnered women are questioned or pitied.

Academic evidence confirms this. A BMC Psychology study (2021) found that stigma around singlehood negatively affects wellbeing, with women who internalise these judgements reporting greater depressive symptoms. This aligns with DePaulo’s (2011, 2023) critique of “singlism” as a systemic prejudice.

Financially, trauma-driven singleness can intensify precarity. Single mothers leaving abusive partners are at heightened risk of poverty due to wage gaps, childcare burdens, and lack of spousal pensions (McKee, 2020). Protective singleness therefore offers emotional safety but can amplify economic vulnerability.

Critical Evaluation

Protective singleness highlights the complexity of interpreting single women’s lives. On one hand, it is an expression of agency, resilience, and survival. On the other, it reveals the enduring harms of trauma and the slow pace of cultural change.

Recent research shows that trauma survivors are more likely to avoid relationships, not because of deficiency but because autonomy protects against revictimisation (Smith et al., 2025). Yet stigma persists, creating additional burdens. The paradox is that singleness can both safeguard women from harm and expose them to new forms of financial and cultural vulnerability.

Conclusion

Protective singleness underscores the entanglement of trauma and autonomy. Women who have experienced abuse or neglect often embrace singleness as a path to safety, resisting dependence or coercion. Intergenerational trauma reinforces these patterns, while feminist critiques situate them within broader structures of patriarchy.

Singleness in this context is not lack, but survival. It is a testimony to resilience and autonomy in a world where relationships can still carry risk. Yet until society addresses stigma, economic penalties, and cultural suspicion, protective singleness will remain both empowering and costly.

References

- Anderson, D.K. and Saunders, D.G. (2003) ‘Leaving an abusive partner: An empirical review of predictors, the process of leaving, and psychological well-being’, Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 4(2), pp. 163–191.

- BBC Worklife (2022) ‘Single shaming: Why people jump to judge the un-partnered’. BBC Worklife, 5 April. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/worklife/article/20220405-single-shaming-why-people-jump-to-judge-the-un-partnered (Accessed: 8 October 2025).

- BMC Psychology (2021) ‘Singlehood stigma and mental health outcomes’. BMC Psychology, 9, 75. Available at: https://bmcpsychology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40359-021-00635-1 (Accessed: 8 October 2025).

- Budgeon, S. (2016) ‘The “problem” with single women: Choice, accountability and social change’, Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33(3), pp. 401–418.

- Colman, R.A. and Widom, C.S. (2004) ‘Childhood abuse and neglect and adult intimate relationships: A prospective study’, Child Abuse & Neglect, 28(11), pp. 1133–1151.

- Danieli, Y. (1998) International Handbook of Multigenerational Legacies of Trauma. New York: Springer.

- Delphy, C. (1984) Close to Home: A Materialist Analysis of Women’s Oppression. London: Hutchinson.

- DePaulo, B. (2011) Singlism: What it is, Why it Matters, and How to Stop it. DoubleDoor Books.

- DePaulo, B. (2023) ‘Single and flourishing: Transcending the deficit narratives of single life’, Journal of Family Theory & Review, 15(3), pp. 389–411.

- Felitti, V.J. et al. (1998) ‘Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study’, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), pp. 245–258.

- Guardian (2024) ‘Young single women lonelier than ever as community declines’. The Guardian, 21 August. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/article/2024/aug/21/young-single-women-lonelier-than-ever-community (Accessed: 8 October 2025).

- Holcombe, L. (1983) Wives and Property: Reform of the Married Women’s Property Law in Nineteenth-Century England. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Kislev, E. (2019) Happy Singlehood: The Rising Acceptance and Celebration of Solo Living. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- McKee, K. (2020) ‘The precarity of single women’s housing’, Housing Studies, 35(6), pp. 967–985.

- Moore, J. and Radtke, H.L. (2015) ‘Managing the tensions of singleness: Women’s lived experiences’, Feminism & Psychology, 25(2), pp. 207–223.

- Reynolds, J. and Wetherell, M. (2003) ‘The discursive climate of singleness: The consequences for women’s negotiation of a single identity’, Feminism & Psychology, 13(4), pp. 489–510.

- Shanley, M.L. (1989) Feminism, Marriage, and the Law in Victorian England, 1850–1895. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Smith, K., Johnson, A. and Patel, R. (2025) ‘Childhood interpersonal trauma and adult relational avoidance’, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 40(7), pp. 1234–1256.

Leave a comment