Introduction

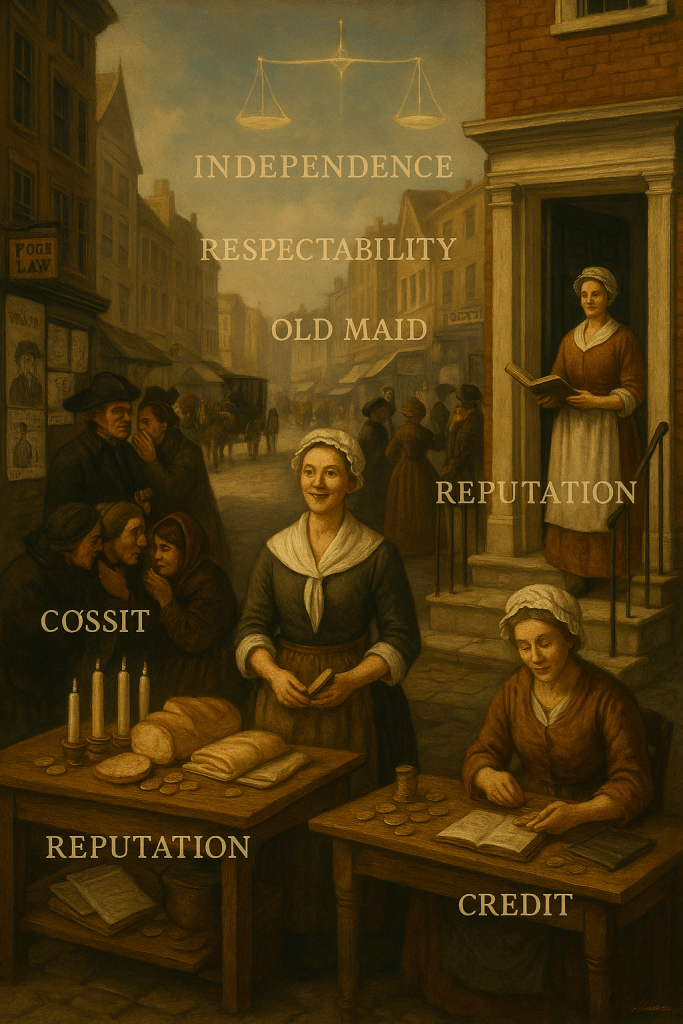

The eighteenth century marked a turning point in the history of single women. Demographic change, urban growth, and the spread of market economies ensured that unmarried women were increasingly visible in towns and cities. They worked as shopkeepers, lodging-house managers, creditors, and petty traders, sustaining everyday economic life. Yet this visibility was accompanied by deepening cultural stigma. Whereas bachelors could be celebrated as independent and sociable, unmarried women were often represented as “old maids” whose singleness implied failure or eccentricity. The eighteenth century therefore illustrates both the practical independence of single women and the moral surveillance that sought to contain it.

Demography and the “Problem” of Single Women

Demographic studies show that singleness was not rare. In some parishes, between 15 and 20 per cent of women remained unmarried for life (Hufton, 1984). Many more spent long stretches of adulthood single, either before marriage or after widowhood. This produced a substantial population of women who lived outside marriage.

Their numbers, however, provoked cultural anxiety. Unmarried women were seen as anomalous in a society that idealised family households as the foundation of order. The persistence of single women into later life became associated with misfortune, idleness, or “failure” to fulfil gendered expectations. In this period, the stereotype of the “old maid” became entrenched in both literature and popular culture (Hill, 1992).

Economic Roles of Single Women

Shopkeeping and petty trade

Single women operated small shops selling food, cloth, candles, and second-hand goods. Court and taxation records show them as both debtors and creditors, indicating their participation in neighbourhood credit networks (Goddard, 2019). Their businesses were often modest but essential to urban provisioning.

Lodging-house keepers

Many widows and spinsters managed lodging houses, which were crucial in expanding towns. These enterprises allowed women to generate income from property, whether rented or inherited. Respectability was central to success: lodging-house keepers relied on reputation to attract tenants and avoid association with immorality (Earle, 1989).

Credit and reputation

Reputation remained the cornerstone of single women’s financial agency. Without guild membership or large capital, they depended on local trust to obtain credit, purchase goods, and sustain businesses. Litigation records suggest that women defended their reputations vigorously in court, aware that loss of trust could ruin their livelihoods (Erickson, 1993).

Widows and Never-Married Women

Widows were typically better positioned than never-married women, as they often inherited capital, stock, or workshop rights from their late husbands. Hufton (1984) highlights that widows could use these resources to maintain businesses or invest in property.

Never-married women, by contrast, usually entered commerce through savings from domestic service. Service offered young women training in literacy, numeracy, and business routines, which could later be used to establish small enterprises (Hill, 1992). This pathway was viable, but precarious, as it relied on savings and personal initiative without the backing of inheritance or guild connections.

Cultural Representations and the “Old Maid”

The eighteenth century consolidated the cultural stereotype of the “old maid.” Literature and satire depicted spinsters as pitiable, bitter, or ridiculous. Plays and pamphlets circulated images of women who had “failed” to marry, presenting them as cautionary examples (Hill, 1992).

This cultural policing contrasted sharply with representations of bachelors. Men who remained single could be framed as sociable, witty, or even desirable. The language of “eligible bachelor” implied potential, whereas “spinster” implied deficiency. The asymmetry reveals how singleness was coded differently for men and women, reinforcing the patriarchal assumption that women’s value lay in marriage and reproduction.

Respectability and Surveillance

Respectability was the key currency for single women. Without the protection of husbands, they needed to demonstrate moral propriety to secure credit, maintain clients, and avoid accusations of immorality. Earle (1989) emphasises that singlewomen were disproportionately visible in court records, reflecting both their economic activity and the scrutiny they faced.

The eighteenth-century poor laws also reinforced suspicion of single women. Those without steady incomes risked being categorised as vagrants or paupers. Parish authorities often regarded spinsters as potential burdens, subjecting them to regulation even when they were independent. Thus, the independence of single women was tolerated but carefully monitored.

Critical Evaluation

The eighteenth century reveals the paradox of single women’s independence and respectability. On one hand, unmarried women were indispensable to urban economies, providing labour, services, and credit. On the other, they were increasingly burdened by cultural stereotypes and moral surveillance. Widows with inheritance were somewhat respected, while never-married women faced harsher suspicion.

Historians should therefore recognise both the structural presence and the structural vulnerability of single women. Their visibility made them targets of satire and regulation, yet their economic contributions made them indispensable. The tension between independence and respectability would continue into the nineteenth century, when coverture and property reform reshaped women’s legal and financial status.

Conclusion

In the eighteenth century, single women were both integral to urban economic life and subject to cultural derision. They ran shops, managed lodging houses, lent money, and contributed to neighbourhood credit systems. At the same time, they were labelled “old maids,” watched closely by parish authorities, and excluded from many formal institutions. Their lives illustrate how independence could coexist with stigma, and how respectability was both their most valuable resource and their greatest vulnerability.

References (Harvard style)

Earle, P. (1989) The Making of the English Middle Class: Business, Society and Family Life in London, 1660–1730. London: Methuen.

Erickson, A.L. (1993) Women and Property in Early Modern England. London: Routledge.

Goddard, R. (2019) ‘Female merchants? Women, debt, and trade in later medieval England c. 1300–c. 1500’, Journal of British Studies, 58(4), pp. 683–708.

Hill, B. (1992) Women, Work and Sexual Politics in Eighteenth-Century England. London: Routledge.

Hufton, O. (1984) ‘Women without men: Widows and spinsters in Britain and France in the eighteenth century’, Journal of Family History, 9(4), pp. 355–376.

Earle, P. (1989) The Making of the English Middle Class: Business, Society and Family Life in London, 1660–1730. London: Methuen.

Erickson, A.L. (1993) Women and Property in Early Modern England. London: Routledge.

Goddard, R. (2019) ‘Female merchants? Women, debt, and trade in later medieval England c. 1300–c. 1500’, Journal of British Studies, 58(4), pp. 683–708.

Hill, B. (1992) Women, Work and Sexual Politics in Eighteenth-Century England. London: Routledge.

Leave a comment