When we speak about violence against women and children, there is often a myth whispered in the background: that danger is confined to youth. Once women pass a certain age, surely they are less at risk? Yet the data tells a very different, sobering story. There is no age at which women are free from violence, whether sexual assault or homicide.

The patterns of sexual violence

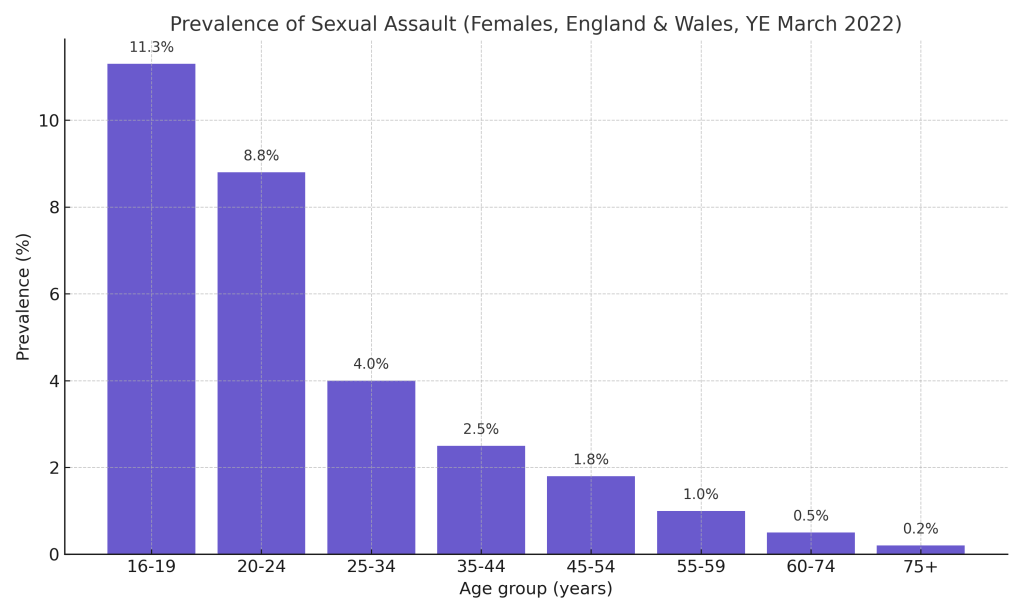

The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) shows that sexual assault is most prevalent among younger women. In the year ending March 2022, an estimated 11.3% of women aged 16–19 and 8.8% of women aged 20–24 reported experiencing sexual assault in the past year. Across all women aged 16+, around 3.3% experienced sexual assault (ONS, 2023).

📊 Figure 1. Prevalence of sexual assault among women by age group (ONS, YE March 2022)

The persistence of risk across the lifespan underlines how ageist assumptions can obscure vulnerability. Services have historically been designed around younger women, but older survivors are often left invisible in policy and practice.

Risk declines in later decades, but it does not disappear. Women in their forties, fifties and sixties still report victimisation, and since the CSEW removed its upper age limit in 2021, it is clear that older women are not immune (ONS, 2023).

The survey also highlights relationship patterns. Female rape victims were most likely to be assaulted by an intimate partner (46%), whereas male rape victims were most likely to be attacked by an acquaintance (38%). This underlines the importance of gender in shaping not just risk but also the relationship context of sexual violence (ONS, 2023).

Homicide: a gendered and age-dispersed crime

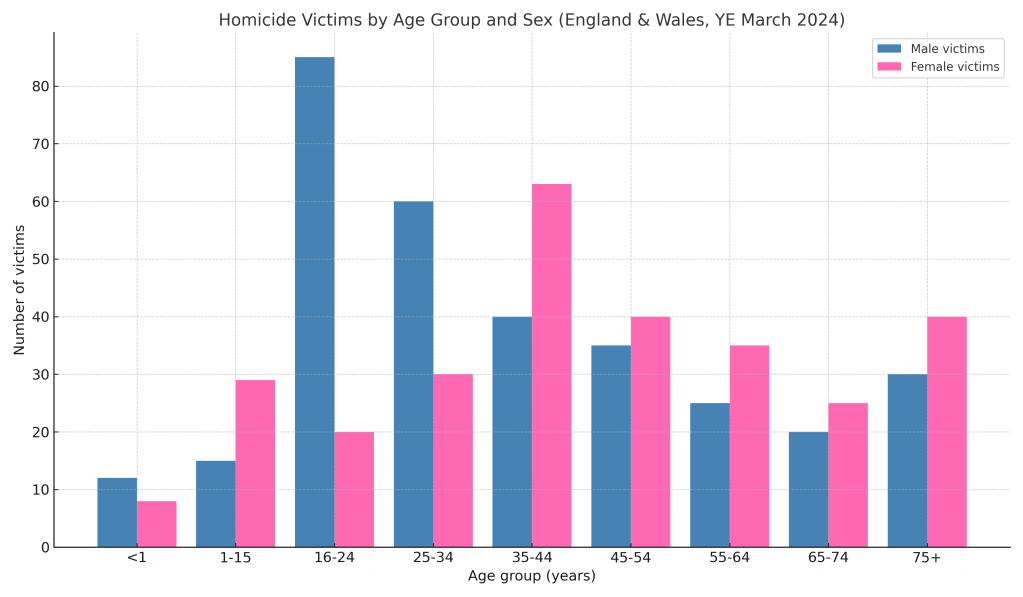

The homicide data paints a complementary picture. In England and Wales in the year ending March 2024, there were 570 homicide victims; 156 were women (ONS, 2025). For men, risk clustered in the 16–24 and 25–34 age bands, often involving sharp instruments such as knives in public settings. For women, however, the story is different: homicide risk is spread across adulthood, peaking in the 35–64 age bands and rising again in later life.

📊 Figure 2. Homicide victims by age group and sex (ONS, YE March 2024)

The Femicide Census has long highlighted that around one in eight women killed by men are aged 70 or older, a figure that shocks many who assume violence wanes with age (Femicide Census, 2025).

How homicide happens

When we look at methods, the picture is starkly gendered. The leading method of homicide overall is the use of a sharp instrument (46%), followed by hitting or kicking, strangulation, and shootings (ONS, 2025).

- Men are most often killed with knives.

- Women are most often killed by strangulation or suffocation, frequently in domestic contexts.

📊 Figure 3. Homicide methods by sex (ONS, YE March 2024)

When broken down by age, these differences sharpen:

- Young men (16–24) overwhelmingly die from knife attacks.

- Women over 45 are disproportionately killed by strangulation, often by partners or ex-partners.

📊 Figure 4. Homicide methods by age and sex (ONS, YE March 2024)

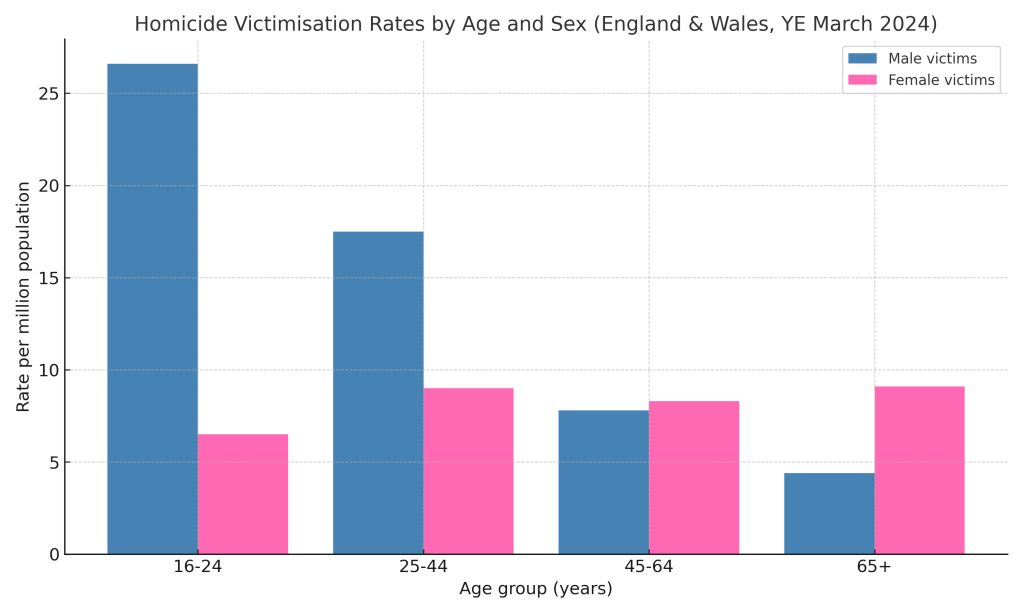

Rates versus counts

It is tempting to focus on raw numbers, but rates per million population tell the fairer story. When adjusted for population:

- Young men (16–24) face the highest homicide rates, reflecting knife crime in public settings.

- Women’s rates remain consistent across adulthood and even rise in later life, reflecting persistent domestic homicide risks.

📊 Figure 5. Homicide rates per million population by age and sex (ONS, YE March 2024)

Ethnicity and homicide: who are the victims, who are the suspects?

Ethnicity adds another layer to this analysis.

In homicides where victim ethnicity was recorded in the year ending March 2022, 74% of victims were White, 14% Black, and 13% from other ethnic groups. When adjusted for population size, homicide rates were around four times higher for Black people compared with White people (MoJ, 2022).

📊 Figure 6. Homicide victims vs suspects by ethnicity (ONS YE Mar 2024; CJS 2019–22)

Asian groups make up around 9% of victims and 10% of suspects, broadly aligned with population share. “Other/unknown” categories reflect both mixed ethnicities and missing data.

Among Black homicide victims, a striking 87% were male, compared with 69% of White victims. Method also varies by ethnicity. Sharp instruments were used in 66% of homicides involving Black victims, compared with 35% of White victims. In contrast, White victims were more likely to be killed by hitting or kicking (21% vs 7–8% for Black or other groups). Black and other group victims were more likely to be killed by strangers, whereas White victims were more often killed by acquaintances or friends (MoJ, 2022).

These disparities require careful interpretation. They do not mean that one ethnic group is “more violent” than another, but they do reveal how structural inequalities, deprivation, and social contexts place certain communities at greater risk of both victimisation and involvement in serious violence. Missing or inconsistent ethnicity recording also complicates the picture.

No safe age, no simple answers

The combined lesson of sexual assault, homicide, and ethnicity data is clear:

- Sexual violence peaks early, but persists throughout life.

- Homicide risk is contextual: public and peer violence for young men, domestic femicide for women of all ages, including older age.

- Ethnicity matters, not as a biological determinant, but as a lens into structural inequality and social harm. Black communities, in particular, face a disproportionate burden of both victimisation and suspicion.

There is no “safe” age, nor a “safe” identity, that shields women or children from violence. Violence may change form, but it does not evaporate at 59, 69, or even 79.

Call to Action: Seeing the Whole Picture

The evidence is unambiguous: violence against women and children is not confined to youth, nor does it disappear with age. Sexual assault peaks in adolescence and early adulthood but persists into older age, and homicide against women is distributed across the life course, often rooted in domestic settings. For men, public violence with knives dominates, especially among the young. These gendered and age-specific patterns are not random, they reflect structural inequalities, cultural norms, and policy blind spots that have allowed violence to continue unchallenged.

Critically, policy responses have been reactive and fragmented. Knife-crime strategies target young men without fully addressing the socioeconomic drivers of violence, while domestic homicide reviews too often focus on individual failings rather than the systemic neglect of women’s safety across the lifespan. The data makes it clear that piecemeal approaches are insufficient.

act on this evidence, three urgent steps are needed:

- Age-inclusive safeguarding: Services and policies must acknowledge that women in their fifties, sixties and seventies face real risk. Ending the silence around older victims requires expanding resources, training, and visibility.

- Gender-aware prevention: Strategies must recognise that male and female homicide risks differ, public space interventions for young men, domestic/intimate partner prevention for women across adulthood. One-size-fits-all approaches fail.

- Structural accountability: Violence is not only an individual crime but a symptom of inequality. Addressing it demands tackling poverty, housing insecurity, coercive control, and systemic misogyny, not merely policing.

- Ethnicity-conscious policy: Data shows Black communities are disproportionately affected. Addressing this means tackling poverty, racism, and inequality, not fuelling stereotypes.

The challenge is not that we lack data. As the Office for National Statistics and Femicide Census demonstrate, the numbers are plain. The challenge is whether we choose to see the whole picture and to act on it. There is no safe age, no point at which vigilance can relax.

If you are a policymaker, practitioner, or educator reading this, the responsibility is yours: integrate this evidence into your practice, your classrooms, and your policies. If you are a reader, the responsibility is shared: speak up against myths, support survivors, and demand that governments resource prevention across the life course.

Silence has never kept women safe. Action, rooted in evidence and justice, might.

References

- Office for National Statistics (2023) Sexual offences victim characteristics, England and Wales: year ending March 2022. Newport: ONS. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/sexualoffencesvictimcharacteristicsenglandandwales/yearendingmarch2022

- Office for National Statistics (2025) Homicide in England and Wales: year ending March 2024. Newport: ONS.

- Femicide Census (2025) Femicide Census Report. London: Femicide Census.

- Ministry of Justice (2022) Statistics on Ethnicity and the Criminal Justice System 2022. London: MoJ. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/ethnicity-and-the-criminal-justice-system-2022/statistics-on-ethnicity-and-the-criminal-justice-system-2022-html

Leave a comment