Introduction

The next decade promises seismic shifts in reproductive technology, gender identity policy, labour markets, and women’s rights. Recent headlines claim that China has invented a humanoid “pregnancy robot” capable of carrying babies to term, while medical transitions are increasingly sophisticated. Yet the gap between media hype and scientific reality remains wide. This essay critically analyses what 2035 might look like for women, distinguishing between speculation and evidence, and asking who controls these technologies and to what end.

Reproductive Technologies: Beyond the Hype

Artificial wombs and ectogenesis

Media reports claiming China has already developed a pregnancy robot overstate current capabilities. Legitimate scientific progress has occurred: the Weizmann Institute sustained mouse embryos in an artificial womb (Weizmann Institute, 2022), and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s “biobag” supported extremely premature lambs (CHOP/FDA, 2023). The US FDA has since explored regulatory pathways for human neonatal trials (EMBO Reports, 2024). However, these technologies are directed at extremely preterm infants, not full-term human gestation. By 2035, partial ectogenesis may enter neonatal intensive care practice, but full human ectogenesis remains a distant prospect.

Uterine transplantation and IVG

In February 2025, the UK celebrated its first live birth after a womb transplant (Womb Transplant UK, 2025). For women with uterine factor infertility, this marks a breakthrough. Meanwhile, in-vitro gametogenesis (IVG) is advancing in animals, but UK bioethics councils caution that human clinical use remains at least a decade away (Nuffield Council on Bioethics, 2024).

Implication: These technologies expand reproductive options but do not erase the centrality of women’s bodies in reproduction.

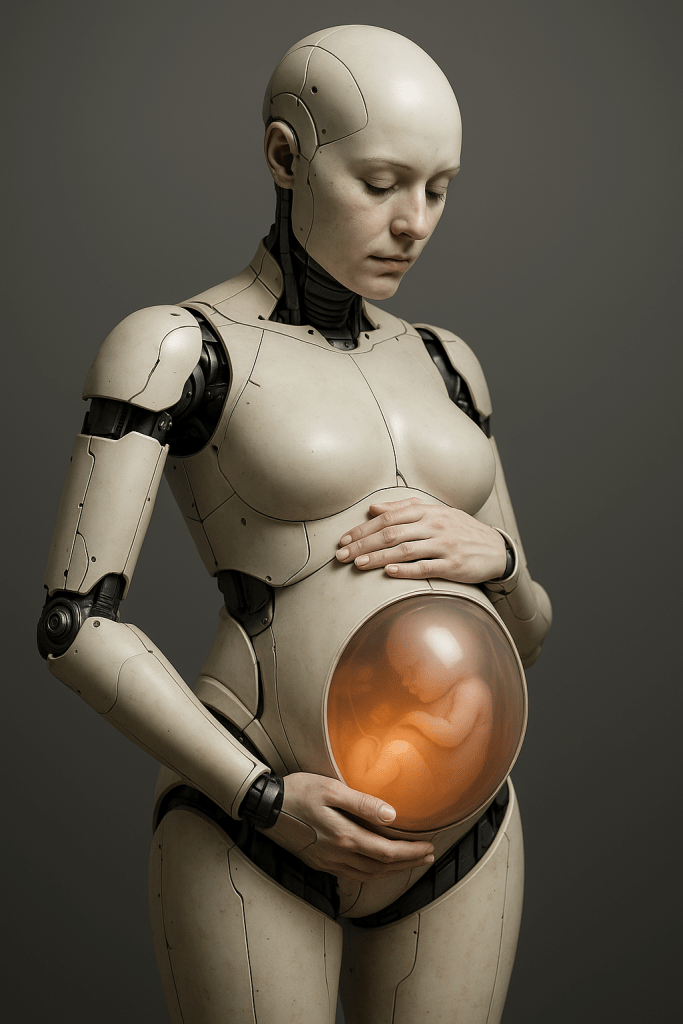

The “Pregnancy Robot” Hype

Media claims

In August 2025, international outlets including New York Post and Times of India reported that Kaiwa Technology, a company in Guangzhou, is developing a humanoid robot with an embedded artificial womb capable of carrying human babies to term, with a prototype targeted for 2026 and a projected cost of US $14,000 (Times of India, 2025; New York Post, 2025). Reports describe nutrient-delivery systems, AI monitoring, and ongoing discussions with Guangdong authorities about ethics and regulation (Mother.ly, 2025; Interesting Engineering, 2025).

Critical analysis

However:

- No independent verification of the claims exists; fact-checkers warn that the reports are unverified and possibly sensationalist (Snopes, 2025).

- Scientific evidence still limits ectogenesis to premature rescue cases, not full-term gestation (CHOP/FDA, 2023; EMBO Reports, 2024).

- Chinese law restricts embryo research to 14 days and bans surrogacy, meaning significant legal reforms would be required (Robotics & Automation News, 2025).

- Ethically, critics argue that mechanising pregnancy risks devaluing women’s embodied reproductive labour and commodifying human gestation (CBC Network, 2025).

Conclusion: Whether fact or hype, the “pregnancy robot” narrative functions as a cultural flashpoint. It shapes how the public imagines reproduction, even before technology exists. The key issue is not technical feasibility but whether such developments are guided by women’s rights and reproductive justice.

Law, Policy, and Women’s Rights

Gender medicine

The Cass Review (2024) has restructured NHS gender services, limiting puberty blockers to research settings and closing Tavistock GIDS (BMJ, 2024). From April 2025, new regional hubs will provide multidisciplinary assessment (NHS England, 2024). This trajectory emphasises evidence-based caution.

Sport, prisons, and single-sex services

World Athletics (2023), UCI Cycling (2023), and World Aquatics (2023) now bar athletes who have undergone male puberty from competing in women’s categories. In UK prisons, transgender women with male genitalia or sexual/violent offences are generally excluded from the female estate (Ministry of Justice, 2023). Crucially, in 2025 the UK Supreme Court ruled that “sex” in the Equality Act means biological sex (Supreme Court, 2025), clarifying protections for single-sex services.

Abortion rights

In June 2025, UK MPs voted to end criminal penalties for women who self-manage abortions, reframing abortion as healthcare, not crime (Reuters, 2025). This is a major shift toward reproductive justice.

Labour Markets and AI

Automation and women’s work

The IMF (2024) estimates that 40% of jobs in advanced economies are exposed to AI, with clerical roles—where women are over-represented, particularly vulnerable. The ILO (2023) warns that without intervention, AI could widen gender inequality.

Roles less susceptible to AI

However, not all women’s work is at risk. Professions requiring manual dexterity, in-person care, or complex relational skills, such as nursing, teaching, early years education, and skilled trades, are far harder to automate (Microsoft Research, 2024; Tom’s Guide, 2024). These sectors, already heavily feminised, may in fact grow in importance as societies age and care demand increases.

Academic performance: girls outperforming boys

Education outcomes provide further resilience. In the 2025 GCSE results, 24.5% of girls achieved Grade 7 (A equivalent) or above, compared with 19.4% of boys, a 5.1 percentage point gap, the smallest since 2000 but still in girls’ favour (The Guardian, 2025; Sky News, 2025). This academic advantage creates opportunities for women to thrive in higher education and adapt to labour-market changes.

Barriers: numeracy confidence

Despite strong academic performance, women are underrepresented in numeracy-heavy jobs. Around a third of women avoid maths-intensive roles due to confidence, not ability (Financial Times, 2024). This cultural barrier hampers entry into STEM and AI-related careers, even though girls outperform boys academically.

Implication: Women’s economic resilience depends on leveraging strengths in care work and education while dismantling barriers to STEM participation.

Gender pay gap and care economy

The UK gender pay gap stood at 7% in 2024 (ONS, 2024). Investing in the undervalued care economy could both close this gap and address demographic ageing (WHO/ILO, 2023).

Health and Maternal Safety

Despite advances, pregnancy carries risk. The UK maternal mortality rate in 2020–22 was 13.56 per 100,000 maternities, with mental health the leading cause of late deaths (MBRRACE-UK, 2025). These realities underline that women’s healthcare systems must not be undermined by speculative promises of artificial reproduction.

Digital Harms

The rise of deepfake-enabled sexual image abuse disproportionately targets women. The UK’s Online Safety Act (2023) introduced new offences, and in 2025 the government confirmed criminalisation of explicit deepfakes (UK Government, 2025). Enforcement capacity will determine whether this protects women meaningfully.

Plausible 2035 Futures for Women

- Neonatal Rescue Becomes Routine: Artificial wombs reduce preterm mortality but do not replace pregnancy.

- Care Economy Renaissance: Labour shortages elevate care work, narrowing pay gaps.

- Platformised Reproduction: Without legal reform, fertility markets expand alongside risks of exploitation.

- Legal Clarity on Sex: Biological sex becomes the baseline in law, while anti-discrimination protections endure.

- AI Polarisation with Resilience: Routine jobs decline, but women thrive in less automatable care roles and through strong educational foundation

Conclusion

By 2035, women’s futures will depend less on the speculative rise of pregnancy robots and more on policy, education, and labour-market choices. Girls’ consistent academic advantage and the resilience of care-oriented roles show that women are not destined to lose ground to AI. The challenge is ensuring policy aligns with these strengths: supporting STEM pathways, valuing care, safeguarding rights, and ensuring new technologies are shaped by, not imposed upon, women.

References

BMJ (2024) ‘Gender healthcare: Six new services for children and young people’, BMJ, 386, q1765.

CBC Network (2025) ‘Mechanised womb? Why pregnancy robots threaten humanity’.

CHOP/FDA (2023) Regulatory considerations for devices intended to support ex-utero foetal development.

EMBO Reports (2024) ‘Artificial womb technology: science, ethics and regulation’, EMBO Reports.

Equality and Human Rights Commission (2025) UK Supreme Court ruling on “sex” in Equality Act 2010.

IMF (2024) Generative AI in advanced economies: labour market exposure and policy.

International Labour Organization (2023) Generative AI and jobs: gender implications.

Interesting Engineering (2025) ‘China’s first pregnancy robot: innovation or dystopia?’.

Law Commission of England and Wales & Scottish Law Commission (2023) Building families through surrogacy: a new law.

MBRRACE-UK (2025) Maternal mortality report 2020–22. Oxford: NPEU.

Ministry of Justice (2023) Policy framework on transgender prisoners.

Mother.ly (2025) ‘China develops pregnancy robot to aid infertile families’.

New York Post (2025) ‘‘Pregnancy robots’ could give birth to human children in revolutionary breakthrough’.

NHS England (2024) Response to the Cass Review: service specification.

Nuffield Council on Bioethics (2024) Genome editing, gametogenesis and ethics of reproduction.

ONS (2024) Gender pay gap in the UK: 2024.

Reuters (2025) ‘UK parliament votes to decriminalise women who self-manage abortion’.

Robotics and Automation News (2025) ‘Chinese company developing humanoid robot to give birth: breakthrough or dystopian nightmare?’.

Snopes (2025) ‘Fact check: claims of pregnancy robots giving birth’.

South China Morning Post (2022) ‘AI “nanny” monitors embryos in artificial womb’.

Supreme Court of the United Kingdom (2025) Ruling clarifying “sex” in Equality Act 2010.

Times of India (2025) ‘China’s 2026 humanoid robot pregnancy with artificial womb: revolutionary leap’.

UK Government (2025) Crackdown on explicit deepfakes under Online Safety Act.

Weizmann Institute (2022) Ex utero mouse embryogenesis experiments.

Womb Transplant UK (2025) First UK live birth after womb transplant.

World Aquatics (2023) Sex eligibility policy and open category.

World Athletics (2023) Eligibility regulations for the female category.

WHO/ILO (2023) Investing in the care economy.

UCI (2023) UCI tightens transgender participation rules.

Leave a comment