Introduction

Terrorism not only aims to destroy lives but often reshapes the identity and cohesion of entire communities. The Birmingham pub bombings of 1974 and the London bombings of July 7, 2005 (7/7) stand as stark reminders of violence perpetrated in the name of ideology. While the former is rooted in the nationalist struggle of the Provisional IRA and the latter in radical Islamist extremism, both events led to devastating loss and trauma. However, beyond the immediate devastation, the bombings had long-lasting psychological and social consequences for two distinct minority communities: the Irish in Britain and British Muslims. This paper explores the lived experiences of survivors, the ripple effects on their respective communities, and the systemic failures that exacerbated their suffering. By analysing survivor testimonies and public responses, the study reveals striking parallels in how communities become collateral damage in the aftermath of terror.

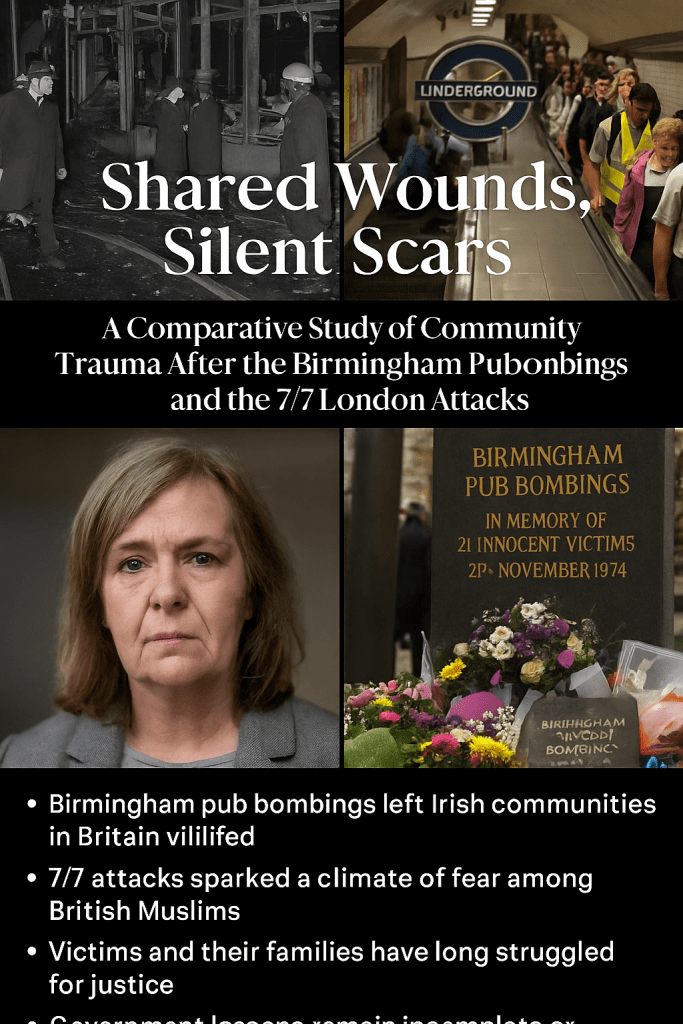

1. The Birmingham Pub Bombings and Their Aftermath

On the evening of November 21, 1974, bombs exploded at the Mulberry Bush and the Tavern in the Town pubs in Birmingham, killing 21 people and injuring over 220. Described by the Morning Advertiser as an “atrocity” that remains burned into the city’s memory, the attack was widely attributed to the Provisional IRA. However, no one has ever been brought to justice for the murders. Survivor Maureen Mitchell recalled, “I was given my last rites… I used to think I was a victim, but I’m a survivor. That took me years.” Her words reflect a psychological transition that many trauma victims undergo, a long, isolated journey toward reclamation of self.

The emotional toll on first responders was equally severe. Firefighter Alan Hill stated, “It’s burnt on my brain… I don’t want these images in my head. It ruins your life.” Yet beyond individual trauma, the bombings inflicted a collective wound on Birmingham’s Irish community. In the days and weeks that followed, Irish pubs and homes were petrol bombed, schools and churches were attacked, and over 2,000 workers at British Leyland walked out following workplace violence between Irish and English staff.

As Julie Hambleton, who lost her sister Maxine in the bombing, said: “We lost our loved ones and then watched Irish communities be vilified.”

Despite years of campaigning, justice remained elusive. The wrongful imprisonment of the Birmingham Six further compounded the grief. A 2016 inquest concluded that the police had failed to act on two prior warnings, and four IRA men believed responsible were never prosecuted.

Government refusal to fund legal support for families echoed systemic indifference, drawing a sharp contrast with support extended to Hillsborough victims. Hambleton described this as a “continuing injustice.”

In 2018, a new memorial featuring three 15-foot steel trees was unveiled. Each leaf reflects a victim’s name onto the pavement when touched by sunlight, symbolising the enduring presence of those lost and the hope for healing. As Birmingham Irish Association CEO Maurice Malone said, the memorial aimed to be “inclusive and healing… reflecting the damage but also the hope.”

2. The 7/7 London Bombings and the Muslim Community Response

On July 7, 2005, coordinated suicide bombings targeted London’s transport system, killing 52 and injuring over 700. The perpetrators were British-born Muslims influenced by Islamist ideology. Survivors of the attack have shared searingly intimate accounts of trauma. Dan Biddle, the most severely injured survivor, recounted sitting inches from one of the bombers before losing both legs and an eye. “I’m not frightened of death,” he said, “but dying alone terrifies me.” To this day, Biddle experiences recurring nightmares and PTSD.

Gill Hicks, another survivor, lost both legs but transformed her trauma through performance art. Her one-woman show Still Alive (and Kicking) reflects a powerful reclaiming of identity: “My identity was reduced to a label, ‘female, unknown, estimated age 30.’ But I rebuilt who I was, piece by piece.” Meanwhile, Mustafa Kurtuldu, a British Muslim survivor, was not just forced to recover from the physical and emotional trauma of the attack but also had to publicly defend his faith, stating that being interrogated on television was a “second trauma.”

The Muslim community, like the Irish decades earlier, faced widespread suspicion and hostility. Hate crimes surged. Tell MAMA reported a 73% increase in Islamophobic incidents in 2024 alone. Media coverage often amplified fear through graphic and moralising language, portraying Muslim perpetrators as “fanatics” and “jihadists.” Gabriella Holt’s discourse analysis found that unlike IRA bombings, where perpetrators were contextualised politically, the 7/7 bombers were framed through a lens of moral depravity.

The PREVENT strategy, introduced as part of the UK’s counter-terror response, further entrenched mistrust. British Muslims became the focus of surveillance, often based on appearance or religious expression. The result was what scholars have called “state-enabled racialisation”, a process that deepens alienation and undermines community cohesion.

3. Comparative Analysis: Parallels and Divergences

Both the Irish and Muslim communities in Britain became scapegoats in the wake of terrorism. Following the Birmingham bombings, Irish identity was racialised and criminalised, while in the wake of 7/7, Islam became a symbol of threat in public discourse. Media framing played a pivotal role in both cases. Holt’s study notes that IRA attacks were portrayed using “neutral and political language,” whereas ISIS-related attacks like 7/7 were described using “emotive, violent and moralistic terminology.”

Institutional responses further mirrored each other. In both instances, governments enacted sweeping counter-terror laws that curtailed civil liberties. The Irish were targeted by the Prevention of Terrorism Act (1974) and Muslims by PREVENT and subsequent legislation. Survivors in both communities fought not just to recover from trauma but to correct public narratives and demand recognition. In each case, a community mourned its dead and its place in society.

Where they diverge is in visibility and voice. The Muslim community today has more platforms to speak out but also faces intensified online harassment and securitisation. The Irish community of the 1970s had fewer avenues for redress and bore their trauma in silence, often afraid to even acknowledge their heritage in public spaces.

4. Support and Services for Survivors and Victims’ Families

Birmingham Pub Bombings (1974)

What Was Lacking

- No formal victim support system existed in the 1970s. Trauma counselling, compensation, or psychological services were not systematically offered to survivors or families.

- Survivors like Maureen Mitchell and firefighter Alan Hill struggled with undiagnosed PTSD, depression, and addiction decades later, with no early intervention.

- Families of victims received no state-sponsored legal aid, despite ongoing campaigns for justice.

- The Irish community felt silenced and unable to seek help for fear of further discrimination.

What Was Eventually Offered

- Campaigning by groups like Justice for the 21 led to renewed inquests, partial legal aid, and a memorial in 2018 supported by the Birmingham Irish Association.

- Community-led efforts helped provide some counselling and support, though inconsistently.

7/7 London Bombings (2005)

What Was Offered

- The London Bombings Relief Charitable Fund distributed over £12 million to victims and families.

- NHS trauma units provided immediate medical and psychological care.

- Services like the 7 July Assistance Centre coordinated practical and emotional support.

- Survivors received prosthetics and rehabilitation via the NHS.

What Remained Insufficient

- Long-term mental health support was inconsistent. Survivors continued to experience PTSD with limited follow-up care.

- Muslim victims and families experienced dual trauma: injury and suspicion.

- PREVENT-linked mistrust discouraged some from seeking public services.

Comparative Overview

CategoryBirmingham Pub Bombings7/7 London Bombings

Immediate medical aid Available, but no psychological triage Available through NHS emergency services

Mental health services None provided at the time Mixed provision via NHS and charities

Legal support Denied legal aid; had to campaign Legal aid and inquiries funded

Community trust Broken, Irish community targeted Mixed, Muslims received services but also mistrust due to counter-terror policies

Memorialisation Grassroots led, achieved after 40+ years State-backed and media-supported within a decade

Lessons and Recommendations

- Institutionalise long-term trauma support: Psychological wounds can last decades. Services must be proactive and survivor-led.

- De-politicise support access: Victims should not face stigma or scrutiny due to their ethnic or religious identity.

- Ensure equitable legal support: Bereaved families deserve automatic, state-funded legal representation during inquests.

- Build memorials through consultation: In both cases, survivors wanted collective healing spaces, not just symbolic gestures.

5. What Has the Government Learned Or Failed to Learn?

Despite the passage of decades and evolving counter-terror frameworks, government responses to terrorism have continued to prioritise security at the expense of long-term community recovery and social justice.

What Was Learned

- The creation of formal assistance bodies, such as the 7 July Assistance Centre, showed an improved understanding of the need for immediate survivor support.

- Financial compensation frameworks post-7/7 demonstrated a more responsive approach than in 1974, where victims’ families were largely unsupported.

- Government agencies began incorporating survivor voices into commemoration efforts and public education, as seen in Gill Hicks’ collaborations with policymakers.

What Was Not Learned

- Calls for public inquiry remain unheeded: Survivors of 7/7 have repeatedly urged the government to launch a full public inquiry into the attack and its handling. Despite public support, no such investigation has materialised. No such inquiry has been granted despite widespread support from victims and campaigners.

- Institutional neglect remains cyclical: The denial of legal aid to Birmingham pub bombing families decades later illustrates how state responses often fall short, mirroring past indifference and undermining trust in justice systems.

- State-enabled racialisation persists. The Muslim community, like the Irish before them, has been placed under suspicion via PREVENT and surveillance regimes.

- Public recognition remains inconsistent: While Hillsborough victims secured a public apology and full inquiry, families affected by the Birmingham bombings are still campaigning for equal acknowledgement and truth.

- Mental health support is under-resourced: Both generations of survivors have suffered long-term trauma without consistent or adequate psychological services.

Policy Gaps and Repetition

The legacy of these two attacks shows that lessons have been learned in technical response but not in ethical responsibility. Neither event spurred a permanent, centralised trauma recovery framework, nor has counter-terror legislation been sufficiently balanced against human rights.

As one survivor put it: “We survived the bomb, but we’re still living the consequences every day.”

Conclusion: Memory, Justice, and Collective Healing

The Birmingham and 7/7 bombings illustrate how terrorism’s reach extends far beyond its physical blast radius. The psychological impact on survivors, the erosion of community trust, and the structural failings of the state converge to produce long-term harm. Survivors like Maureen Mitchell and Gill Hicks remind us that trauma is not a single event but a lifelong negotiation of memory, identity, and resilience.

Both the Irish and Muslim communities have shown extraordinary strength, mobilising for justice and visibility in the face of public suspicion and policy-driven marginalisation. Their stories underscore the importance of survivor-centred narratives in national healing. As memorials are built and testimonies are shared, these communities offer us lessons in endurance and humanity.

Future counter-terror strategies must take heed: security must never come at the cost of justice, and no community should bear the burden of crimes it did not commit.

References

- Mann, R. (2018). Irish community behind memorial for Birmingham pub bombings victims. Morning Advertiser.

- Drury, I. (2016). Blow for Birmingham pub bombing families. Daily Mail.

- Holt, G. (2022). Newspaper Discourse: Constructing Representations of Terrorist Groups (IRA and ISIS). Fields: Journal of Huddersfield Student Research.

- Tell MAMA. (2025). Annual Report: Islamophobia in the UK.

- BBC News, ITV News, The Guardian, Independent (2024–2025). Survivor accounts and retrospective features on Birmingham and 7/7 attacks.

- Nasar, A. & Schaffer, C. (2020). Psychological trauma in post-terror Britain. Journal of Social and Mental Health.

- McCarvill, J. (2002). Trauma and memory in post-conflict communities. University of Warwick Thesis.

Leave a comment