Feminist-LGBTQ solidarity refers to the historic alliance between feminist and lesbian activists and the broader LGBTQ+ movement. This collaboration, rooted in shared values of bodily autonomy and civil rights, led to major legal and cultural advances in the mid-20th century. Today, that alliance faces tensions over gender identity, safeguarding, and the erosion of sex-based protections.

Foundations of a United Movement

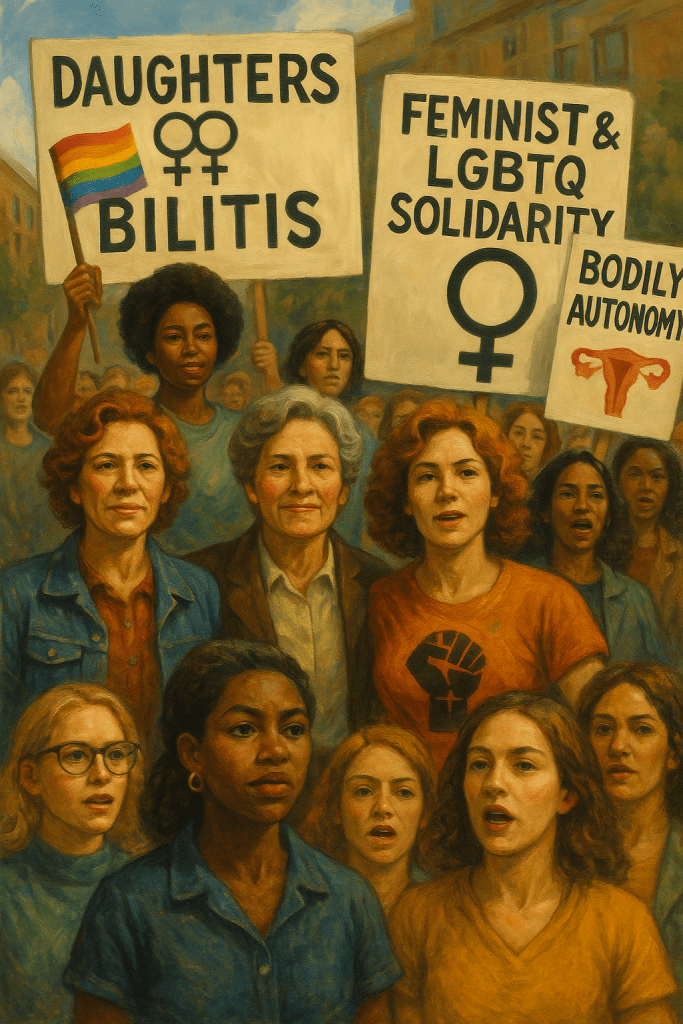

In the mid-20th century, lesbians and feminists were central to the LGBTQ+ rights movement. Pioneering women such as Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin founded the Daughters of Bilitis in 1955, the first American organisation for lesbian women. Initially a social network, the group quickly became politically active, advocating for feminist and LGBTQ+ rights (Miguel and Glover, 2021).

By the 1960s and 1970s, lesbians were increasingly forming independent collectives and pressing mainstream feminist organisations to adopt lesbian rights into their platforms. Jean O’Leary and others, frustrated by male-dominated gay liberation groups, initiated lesbian-focused activism (APA, 2023). This activism encouraged the National Organization for Women (NOW) to form a lesbian rights task force and promote gay rights at major conventions (Radcliffe Institute, 2020).

This intersection of feminist and lesbian activism proved mutually reinforcing. Both movements opposed the legal and social constraints imposed by patriarchal structures. Feminist lawyers filed amicus briefs in gay rights cases, and LGBTQ+ campaigners supported reproductive rights and other feminist causes. As Valk (2019) argues, this period saw the consolidation of a potent feminist–LGBTQ+ alliance that fought collectively for bodily autonomy, sexual freedom, and equality.

Bodily Autonomy as a Shared Principle

At the heart of feminist and LGBTQ+ solidarity was a shared commitment to bodily autonomy. Feminists historically defended the right to make choices about one’s body, especially about reproductive rights, sexuality, and protection from male violence. According to the World Economic Forum, bodily autonomy refers to “authority over making decisions about how your own body is cared for” and is the foundation of feminist ideology (Okamoto in Letzing, 2025).

This principle resonated deeply within LGBTQ+ circles, particularly among lesbians who faced “compulsory heterosexuality” and sought freedom from gendered expectations. Feminist and gay rights movements both opposed legal controls over sex, marriage, and reproduction and jointly campaigned for the decriminalisation of homosexuality and access to reproductive healthcare (Radcliffe Institute, 2020; McShane, 2019). Their shared commitment to self-determination enabled legal victories and shifted public attitudes across the West.

From Material Reality to Identity Politics

However, the close relationship began to fracture in the late 20th and early 21st centuries with the rise of identity politics. While second-wave feminism focused on sex-based oppression, including reproductive risk, domestic violence, and pay inequality, third-wave and queer theorists began to prioritise fluid identity categories. Gender identity increasingly displaced biological sex as the primary category of analysis within LGBTQ+ activism (Valk, 2019).

This shift created tension. Gender-critical feminists argue that women’s oppression is grounded in material realities , being biologically female, and that laws and policies must reflect this. The rise of gender identity, they claim, has obscured the relevance of sex-based rights and led to the erosion of hard-won protections (Murphy, 2022).

On the other hand, queer and trans activists argue that self-identification is a civil rights issue. For them, gender identity is fundamental, and denying transgender individuals access to women’s spaces is a form of discrimination (Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2025). These differing frameworks – one rooted in biology, the other in identity – have generated significant conflict within feminist and LGBTQ+ spaces.

Contemporary Frictions and the “Broken Alliance”

In recent years, disagreements between some feminist groups and mainstream LGBTQ+ organisations have intensified, leading observers to describe a “broken alliance.” Two flashpoints encapsulate these tensions: the question of single-sex spaces and the perceived erasure of lesbian and female voices within the LGBTQ+ umbrella.

Safeguarding Women’s Spaces vs. Inclusion: Many feminists assert that specific spaces, such as women’s refuges, prisons, or changing rooms, must remain single-sex (female-only) for reasons of privacy and safety. They argue that sex (not self-identified gender) should determine access to these spaces, especially given the risk of male violence. However, several LGBTQ+ and trans advocacy organisations take the position that transgender women (who are biologically male) are women and should be included in women’s facilities. This has led to conflict over policies and laws. A recent high-profile legal clarification in the UK backed the feminist perspective on sex-based definitions.

Critics of recent legal clarifications argue that such policies contribute to the stigmatisation of transgender individuals, asserting that the majority of trans women are simply seeking safety, dignity, and social acceptance (Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2025). Conversely, feminist commentators who support these rulings feel affirmed, contending that they uphold the principle of biological sex as the basis for sex-based rights and offer essential safeguards for women’s privacy and dignity (Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2025).

This ideological divide has sometimes manifested in highly charged public confrontations. At the 2018 London Pride march, for instance, a group of lesbians protesting under banners asserting the primacy of female-only spaces and opposing the slogan “trans women are women” were met with hostility from other participants (Bindel, 2023). Similar incidents have been reported across other cities, where lesbian campaigners claim they have been jeered at or silenced for defending sex-based rights (Bindel, 2023).

Many LGBTQ+ organisations today centre transgender inclusion within their ethos, including in contexts traditionally reserved for biological females. However, gender-critical feminists argue that this emphasis on identity often overrides legitimate safeguarding concerns, particularly in environments such as women’s shelters, changing rooms, and prisons (Murphy, 2022). What has emerged is a deeply polarised discourse in which one side foregrounds inclusion and self-identification while the other insists on the material and legal significance of sex. Both speak to fundamentally different understandings of womanhood, often leading to mutual incomprehension rather than constructive engagement (Murphy, 2022).

A 2025 Supreme Court judgment, reinforced by the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC), concluded that the term “woman” under the Equality Act refers to biological sex, not gender identity. It clarified that male-born individuals identifying as women cannot legally access women-only facilities if this compromises safety or privacy (EHRC, 2025). Gender-critical feminists hailed this as a defence of sex-based rights. Nevertheless, many LGBTQ+ organisations criticised the ruling as exclusionary and harmful to trans women (EHRC, 2025).

At the same time, the guidance noted that trans people should not be left without any facilities; where possible, organisations are encouraged to provide gender-neutral options alongside single-sex ones. This nuanced stance reflects the crux of the debate: how to balance transgender inclusion with the safeguarding of women’s rights. Many LGBTQ+ advocacy groups criticised the ruling, viewing it as a setback that prioritises exclusion over inclusion.

Erasure of Lesbian and Feminist Voices:

Another contemporary concern is that lesbian voices, particularly those critical of prevailing gender politics, are being drowned out or censored within LGBTQ+ spaces. Ironically, the movement that once championed lesbian visibility is accused of sidelining lesbians who don’t conform to new norms. Veteran lesbian campaigners like Julie Bindel have spoken out about this trend, noting that “lesbians only appear welcome [in the LGBTQ+ community] if we drop the word [‘lesbian’] so as not to offend” (Bindel, 2023). She and others observe that younger lesbians are often pressured to identify as queer or even to reconsider their sexuality if they express discomfort with aspects of trans activism. In Bindel’s interviews with young lesbians across various countries, many reported feeling coerced to abandon the label lesbian, some saying that the term has been branded transphobic to the point that “women are put off using that label and have gone back into the closet.” This is a striking development, considering that “lesbian” was a proud identity in feminist and gay liberation circles for decades.

The sense of erasure extends beyond terminology. Lesbian activists have faced harassment at pride events for standing under the lesbian banner rather than a more generic queer flag. Moreover, gender-critical feminists, many of them lesbian, have experienced widespread “no-platforming.” Meghan Murphy, a prominent Canadian feminist writer, describes how since the mid-2010s, women who tried to warn of potential harms in gender-identity policies were “actively silenced: blacklisted by the media, ostracised by the left, and no-platformed at universities.(Murphy, 2022)” She recounts that their speaking events were often cancelled due to pressure, venues denied them space, and articles questioning gender ideology were pulled from publication. Even book deals were terminated for those writing from a critical feminist perspective on these issues.

Such accounts illustrate a climate in which expressing certain feminist viewpoints (especially those critical of the inclusion of male-bodied people in all women’s spaces or of the concept of innate gender identity) can result in harsh professional and personal penalties. The bisexual community has also voiced feelings of marginalisation in the current milieu. As one bisexual activist lamented, “People often disregard bisexual people or assume every bisexual is the same… This, for me is the most heartbreaking thing of all” (Henry, 2021). This comment reflects how the focus on a simple LGBT versus feminist binary conflict can sometimes overlook nuances , such as the erasure and stereotyping of bisexual identities, in broader discussions of inclusion. In sum, a number of women (lesbian, bisexual, or straight feminist) contend that their perspectives are being erased within progressive circles that once championed free expression. They argue that conformity of thought has taken hold, wherein any dissent from the dominant trans-inclusivity narrative is branded as bigotry, effectively silencing dissenting feminist voices.

On the flip side, trans activists and allies argue that what is characterised as “silencing” is a justifiable response to hate or ignorance. They view many gender-critical positions as fundamentally prejudiced against an already vulnerable trans population. Thus, the clash often devolves into mutual recrimination, with lesbians and feminists accusing the LGBTQ+ movement of betraying its own and trans advocates accusing those feminists of bigotry. The outcome is a deeply fractured discourse, a far cry from the unity seen in earlier decades.

Toward a Reconciliation?

Understanding the history of feminist–LGBTQ+ solidarity makes the current friction all the more poignant. The alliance between feminists (particularly lesbians) and gay rights advocates was instrumental in achieving many of the freedoms Western LGBTQ+ communities enjoy today. That shared legacy suggests common ground exists if both sides can remember their mutual goals. Both feminists and LGBTQ+ activists ultimately seek a society free from gender-based oppression and heteronormative constraints, a society where individuals can live authentically and safely, regardless of sex or sexual orientation. Indeed, voices from within the movements are calling for unity. One researcher examining second-wave feminism and gay liberation observed, “It seems to me like the best way to conquer whatever kind of struggle we have is to come together… Without the feminist movement backing the gay rights movement, I don’t think we would have these foundational legal victories for gay rights” (Campbell,2020). Remembering this “thick of it” collaboration might be key to moving forward. Any path to reconciliation would likely involve frank dialogue and a willingness to compromise on both sides.

Conclusion: A Fragmented Alliance in an Ideologically Engineered Landscape

The historical alliance between feminists, particularly lesbians, and the broader LGBTQ+ movement was once a cornerstone of civil rights progress. Grounded in a shared resistance to patriarchal oppression and a mutual defence of bodily autonomy, it delivered some of the most significant legal and cultural gains of the late 20th century (Campbell, 2020; Valk, 2019). However, today, that solidarity has fractured. Tensions have emerged from cultural shifts and fundamental ideological divergences: one side is grounded in material, sex-based reality; the other is advancing fluid identity as the dominant framework for justice (Murphy, 2022; Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2025).

This rift has not unfolded in a vacuum. As documented in previous sections, it has been materially underwritten by powerful philanthropic actors, most notably the Open Society Foundations (OSF), the Arcus Foundation, and the Ford Foundation, who have strategically invested in gender identity advocacy, shaping institutional norms, legislation, and funding ecosystems to prioritise self-identification frameworks (Ford Foundation, 2023; Open Society Foundations, 2023, Stryker, 2024). These organisations have funded activist networks and influenced the ideological orientation of DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) infrastructure across multiple sectors. The result is an ecosystem where dissenting feminist voices, especially those advocating for sex-based rights, are routinely pathologised, sidelined, or silenced (Bindel, 2023; Murphy, 2022).

What began as a grassroots fight for liberation has partly been co-opted by top-down enforcement of contested ideologies. As Dixon (2022) and others argue, the fusion of philanthropic capital with institutional policy-making has created an orthodoxy in which critical perspectives are marginalised as regressive. Yet, defending women’s sex-based protections is not inherently exclusionary; it is, as many feminists argue, a principled stance grounded in safeguarding, equality, and democratic pluralism (Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2025; Murphy, 2022)

To heal the fracture and move toward renewed solidarity, both feminist and LGBTQ+ movements must engage in mutual recognition of the legitimacy of each other’s concerns. This will require LGBTQ+ organisations to acknowledge that safeguarding based on biological sex is not tantamount to transphobia. Equally, feminist movements must respond sensitively to the lived vulnerabilities of trans individuals. Above all, both must resist the uncritical adoption of donor-driven ideologies and instead recommit to democratic deliberation, transparency, and material realities. Only then can the movement reclaim the radical, inclusive ethos that once united it in a common cause.

References:

APA. (2023) A brief history of LGBT social movements. Available at: https://www.apa.org/topics/lgbtq/history (Accessed: 29 June 2025).

Bindel, J. (2023) Lesbians are being erased by transgender activists. The Spectator. Available at: https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/lesbians-are-being-erased-by-transgender-activists (Accessed: 29 June 2025).

Campbell, C. (2020) In research on feminism and gay rights, a case for unity. Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University. Available at: https://www.radcliffe.harvard.edu/news-and-ideas/in-research-on-feminism-and-gay-rights-a-case-for-unity (Accessed: 29 June 2025).

Equality and Human Rights Commission. (2025) Interim update on UK Supreme Court judgment (For Women Scotland v. Scottish Ministers). Available at: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/media-centre/interim-update-practical-implications-uk-supreme-court-judgment (Accessed: 29 June 2025).

Henry, D. (2021) How I became a trans rights activist — then turned “gender critical”. Uncommon Ground Media. Available at: https://uncommongroundmedia.com/how-i-became-a-trans-rights-activist-then-turned-gender-critical (Accessed: 29 June 2025).

McShane, J. (2019) LGBTQ women who made history. Smithsonian Magazine. Available at: https://womenshistory.si.edu/blog/lgbtq-women-who-made-history (Accessed: 29 June 2025).

Miguel, K. and Glover, J. (2021) Lesbian pioneers pave the way for LGBTQ+ rights years before Stonewall. ABC7 News. Available at: https://abc7.com/phyllis-lyon-del-martin-and-daughters-of-bilitis/11085742 (Accessed: 29 June 2025).

Murphy, M. (2022) Where are all the feminists? We’re right here, being erased by you. Feminist Current. Available at: https://www.feministcurrent.com/2022/05/24/where-are-all-the-feminists-were-right-here-being-erased-by-you (Accessed: 29 June 2025).

Okamoto, N. quoted in Letzing, J. (2025) What is women’s “bodily autonomy” and why does it matter? World Economic Forum. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/03/what-is-bodily-autonomy-and-why-does-it-matter-for-women (Accessed: 29 June 2025).

Valk, A. (2019) Lesbian feminism – contemporary issues. Encyclopædia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/lesbian-feminism/Contemporary-issues (Accessed: 29 June 2025).

Leave a comment